Running the Game: Death and How to Live with It

- October 1, 2018

- Articles

- Posted by Josh Trujillo

- Comments Off on Running the Game: Death and How to Live with It

There is nothing players and game masters dread more than the death of a beloved character. These dramatic events happen for a variety of reasons, and are usually unintended by the game master. Death holds the potential to a derail a gaming session—or worse yet, an entire campaign.

I’ve seen a player moved to tears because their paladin was disemboweled by a series of bad rolls. I’ve had players storm out of my apartment in a fit of rage because their choices got their wizard impaled. I’ve seen player characters kill one another over an enchanted artifact, ruining a very real friendship in the process.

Yet I never hesitate to kill off characters, and neither should you!

Death, sacrifice, murder, and betrayal are hallmarks of adventure games. After all, why even have hit points if there’s no risk of them ever dropping to zero? As much as your players should test the boundaries of the elaborate fictional world you’ve constructed, you absolutely must push back with real stakes and consequences. Too often adventure parties devolve into anarchy because game masters are afraid to ruffle feathers. Remember that the players are playing because they want to help you tell your story. However, they also want you to help them tell their story.

Players spend more time filling out a character sheet than they spend doing their taxes. Strengths, weaknesses, personal histories, special abilities, carrying capacity, land speed; all of these can be agonizing choices for the player to make. The idea of potentially losing that character is a big deal, but killing characters doesn’t make you the bad guy. You’re trying to tell an exciting story, and no character is promised a happy ending. It’s not uncommon for my players to be on their second, even third character by the time we reach the end of the campaign.

Once I had a player who, through multiple unrelated failures, lost three characters in three consecutive gaming sessions. It would have been easy for him to turn the players against me, or claim he was being targeted. The truth was he became more reckless with each new character. Each new hero threatened the spirit of the game with behavior that derailed the other players. My only regret is not talking to the player one-on-one earlier. His understanding of the game and its rules was limited. After a lot of discussion, he created a fourth character that fit the campaign better and quickly became a favorite of the party. Thankfully he survived until the end.

That said, there are real risks to killing off player characters. After all, adventure party dynamics are a delicate thing. If you lose your healer, the heroes might not be able to survive an important battle. If you lose your elf, all of the elven lore you wrote into the campaign will go to waste. Most game masters would rather remove that possibility entirely, which I sympathize with. It is terrible to plan a long story arc for your friend only for them to fall into an acid pit on the second session. Much of the preparation I do for my campaigns deals with individual player characters’ stories. It’s a disappointment for me too when I have a great five-session arc planned, only for them to fall into an acid pit in the first hour.

In my twenty years running tabletop RPGs, I’ve killed off too many characters to count. Some were meaningful, important moments that I’ll remember forever. Others were cringeworthy confluences of bad decision making and bad rolls that I still regret. In both types of occasions, I had no choice but to move forward and kill the character. Rules were meant to be broken in roleplaying games, but this is the one I cling desperately to. Thankfully, I’ve developed a few tricks to ease the grieving process.

When a character would be killed according to the rules, I don’t always kill the character. What I do instead is take control of that character away from the player. Perhaps this near-death experience brought out a new personality and new complications to improve a campaign. Memorable NPCs are hard to come by, and this is a great way to “make” one that has an important connection to the remaining adventuring party. I’ve even had occasions where a player lost a character, lost a second one, and ended up reclaiming control of the first hero. That’s the kind of character arc you can only have if you get creative in dealing with death.

When a character would be killed according to the rules, I don’t always kill the character. What I do instead is take control of that character away from the player. Perhaps this near-death experience brought out a new personality and new complications to improve a campaign. Memorable NPCs are hard to come by, and this is a great way to “make” one that has an important connection to the remaining adventuring party. I’ve even had occasions where a player lost a character, lost a second one, and ended up reclaiming control of the first hero. That’s the kind of character arc you can only have if you get creative in dealing with death.

Other times I’ll demand that a replacement character have some sort of meaningful connection to the recently deceased. Fantasy games are littered (and I mean littered) with orphans and royal bloodlines. Be creative and use this new character as a way to flesh out and continue the original character’s story. If Princess Sariah is killed in battle, maybe the next in line for succession will join your heroes. Just because a character is dead doesn’t mean their story, or contributions to the greater story, is over.

Perhaps because I overvalue death as a narrative device in adventure games, I shy away from letting players resurrect one another. The power to control life and death is too great for the sociopaths I run games for. If they think they can run to the local cleric and resurrect Bob the Barbarian anytime he gets killed, it will lead to a much more destructive campaign.

This rule also applies for healing potions, wands, staffs, whatever. Every combat encounter should feel life-threatening, though precious few of them actually are. You eliminate the danger and suspense of combat if you offer your characters with ways to quickly recover from serious injuries. Force your magic users to make the tough decisions about allocating spell slots to healing magic. This balance is fundamental to developing a healthy party dynamic. Make the heroes rely on themselves and one another for solutions rather than looking to you for another handout. If players don’t need to rely on one another, they’ll start to act like it.

Yes, a good RPG is about a lot more than battle damage and hit points. A good NPC can get your players to do a lot more than the threat of death ever could. But for some players, especially new ones, preying on their survival instincts is the most effective way to keep your game running smoothly.

In starting a new campaign, I make a point of trying to kill a player character early on. I’m rarely malicious about it, and I might even let one of my more experienced players in on the twist. I just feel it’s important to set a tone, to establish that losing a character is neither shameful, nor the end of the world. I’m well past the point of trying to make my players cry. I want a fun, humble group that can celebrate our defeats as much as our victories. Plus, nothing seems to bond a disparate group of players together like an iconic or hilarious death.

Even more dreaded than a single character’s death, is the death of an entire party. A Total Party Kill. I try not to include threats with the potential to do so much damage, because players love to punch upwards and throw caution to the wind. If you do want a challenge way out of your team’s weight class, proceed with extreme caution. These types of threats and foes should be at the conclusion of a storyline, building on weeks and months of immersive storytelling. Escalation is key to storytelling. Let them fight goblins on week one, and deities on week fifty. That kind of clear progress is something your players will latch onto when reminiscing about your campaign.

If you want to introduce your campaign arch-villain early on, make sure it’s in a way that the characters can’t pick a fight. Give recurring villains leverage over the player characters, and put them in situations where combat or betrayal would be impossible. I’ve had to restructure campaigns at least a dozen times because every recurring villain I introduce falls victim to a critical hit from one of the players. (Thieves and rogues are especially likely to try and assassinate the arch-boss, so keep an eye on them.) You might not want your arch-villain directly interacting with low-level player characters, even if they are destined to fight later on. The risk there is being forced into a combat situation that the team isn’t yet ready to handle.

That said, some games aren’t made for a body count. Nor are some groups cool with losing a character they’ve grown so invested in. These are vital conversations to have with your players before you start a campaign. Certain storylines demand having every character in play through the duration of the campaign. Cool. A successful game master should be able to keep the tension high without resorting to extreme violence.

If death feels too extreme, there are other types of consequences to lean on. Maybe they lose all of their equipment when they die, or suffer some sort of permanent injury. Losing a limb, limiting their walking speed, or permanently reducing a stat point can be just as effective in making the players understand the stakes involved with their actions. Bankrupting a character might have as much dramatic power as a decapitation. Sometimes these are better for the sake of the gaming table.

My players will always, always, always surprise me. They are much smarter than I am, and some have more time to read and memorize the rules than I do. Situations that I thought would guarantee a massacre don’t always end up that way. Players find technicalities in my ancient prophecies, or workarounds to keep anyone from having to sacrifice themselves to the sand goddess. This is the ebb and flow that makes these games more unique and personalized than anything else. You have to welcome the surprises that come your way, just like you expect the players to. You made this game and if something’s not working, there’s a better-than-good chance that you are responsible.

If you made a dungeon too difficult and killed the entire party, admit it. Reveal that the characters were collectively dreaming a nightmare of the real dungeon, and only now have the experience to survive the encounters. Hackneyed reversals do less damage to a campaign in the long run than a brutal, mean-spirited death. Do what feels right, even if it does mean hitting the reset button.

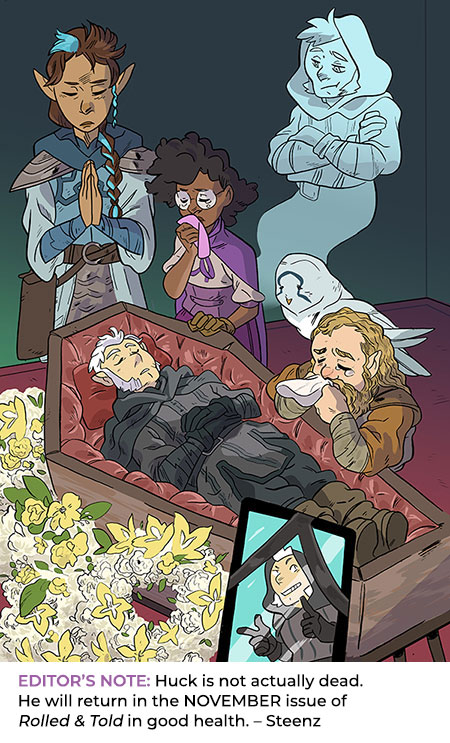

And if all else fails, never forget these two words: Ghost Heroes.

Josh Trujillo is a comic book and video game writer based in Northern California. A lifelong dungeon master, Josh is the creator of DEATH SAVES: FALLEN HEROES OF THE KITCHEN TABLE. @losthiskeysman

Josh Trujillo is a comic book and video game writer based in Northern California. A lifelong dungeon master, Josh is the creator of DEATH SAVES: FALLEN HEROES OF THE KITCHEN TABLE. @losthiskeysman